Preface

The author of this blog has a degree in Psychology and Statistics and a postgraduate degree in Applied, Social and Market Research. Although I don't use psychology on a professional basis, I have retained a strong interest in social psychology and am offering how research may be used more effectively.

"conspiracy theorist" label

The ‘conspiracy theory’ label is being increasingly used in society and by the media as a pejorative and derogatory label, yet the Oxford dictionary defines a conspiracy as “1. A secret plan by a group to do something unlawful or harmful. 2 the action of conspiring.”

Since 19 hijackers allegedly conspired to attack civilians and cause death and harm this would be defined as a conspiracy, yet to what extent it is theory or fact would be determined by an open and independent investigation, something that has not yet been carried out.

As those in the community know, US Government officials involved in the 9/11 Commission, as well as others, have themselves admitted the investigation did not involve full transparency and accountability from important agencies.

9/11 arouses strong emotions and the use of the "conspiracy theory" label implies a person who dismisses such ‘theories’ are threatened by information they do not want to understand and because it involves implications they are too frightened of to contemplate.

The "conspiracy theory" label is used for three reasons. First, it is used as a term of censorship and exclusion of individuals from a group, second, it is a method of deflecting awkward questions about important issues and, third, it is a way of attacking the competence of the person who has the courage to raise disturbing questions, rather than the attacker being able to investigate those very issues for themselves (i.e. being derogatory or condescending).

Bush famously declared, “Let us never tolerate outrageous conspiracy theories regarding the attacks of September 11” and further said, “You are either with us or you are with the terrorists”. Discussion and the examination of the evidence to understand who perpetrated 9/11 was forbidden. Even Obama said in a speech in Egypt on the 4th June 2009 that 9/11 is something to be dealt with, not opinions to be debated. What kind of Government would threaten the entire world into fear and emotional submission in order to proceed with its own global agenda?

A reluctance to investigate

The evidence, anomalies and the serious questions that have arisen and remained unanswered since the attacks of September 2001 and, similarly since the London bombings in July 2005, should convince any open-minded individual that a new investigation is required, indeed, should be demanded for both. Yet why are people so reluctant to look into either of these for themselves? The continuing obstacle of the truth movement is how to engage with the public more effectively.

Solomon Asch and the need to be liked

At heart, we are social animals, we want to have friends and we want to be liked but, under some circumstances, there can be an unfortunate trade-off. Our desire to be liked by others means we may not always want to express an honest opinion. Our behaviour is influenced by forces, some of which we are not even aware. We assume others see the world in the same way as we do, but we do not. We are influenced by what we hear, see, read, what kind of values we grow up with, what we consider to be important in society and how we relate to family, friends, work colleagues and other individuals in our own personally important social groups. Laurie Manwell stated the following in a lecture:

“On the first day of one of my social psychology classes, the professor got up in front of the class and said, ‘I can sum up human behaviour in these three things, and that’s people like to be liked, they like to be right and they like to be free and its in that order. Being liked is number one and they will trade with being right and being free with being liked.’ … The thing about being liked is that the pressure to not violate a social norm is a lot stronger than you think it is”.

Part 1 of Laurie Manwell's lecture

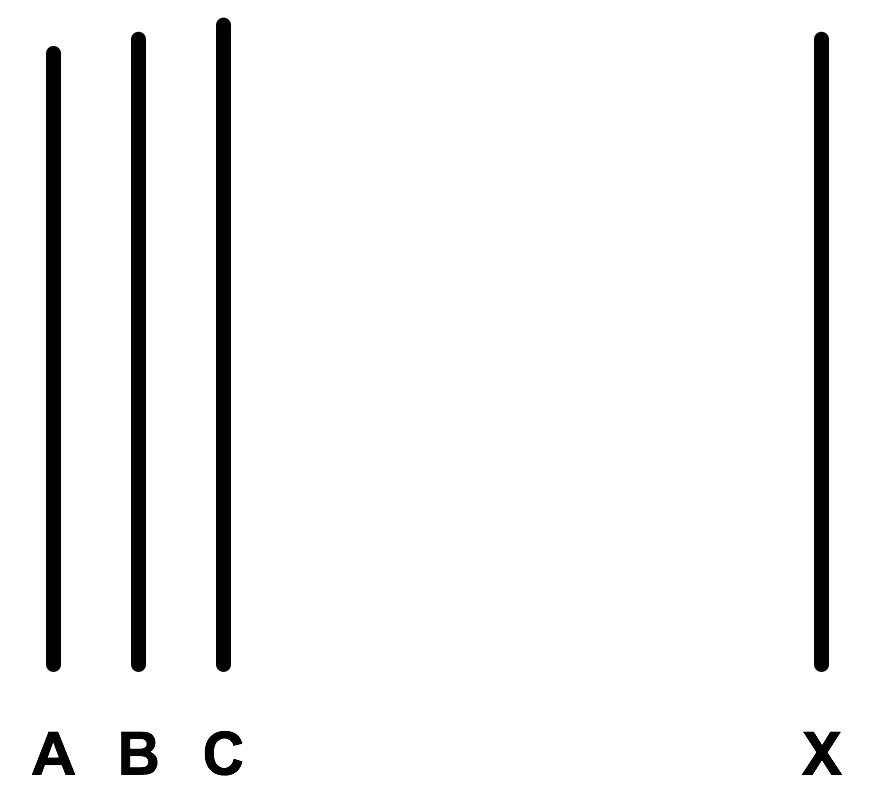

Despite belonging to various social groups, We like to think we are independent in nature and we like to think we are totally in control over how we feel, how we respond to others and what we say. In some circumstances there is a powerful need to conform or we don't like to say things because we don't want to appear foolish. This was demonstrated by Solomon Asch in his classic experiment on what was ostensibly a line-length comparison task in which he presented participants with a test line (x) and to choose a line from a set of options which they thought was the closest in length (A, B, C):

But there was a catch. The initial experiment consisted of only one genuine participant. The rest were confederates in on the ruse. The experiment was set up to look at the power of conformity by testing how a lone genuine participant would respond to deliberate wrong answers given by the confederates. As Manwell stated in the lecture, once a person gives up the need to be right in order to be liked they automatically give up the right to be free. If you are knowingly giving wrong answers, then you are not free. But people don't want to give a wrong answer, so they stay silent.

Demolishing the iconic psychological barriers of 9/11 truth

Laurie Manwell (2007) explains how individuals may find it difficult to investigate 9/11 and how we might engage with others more constructively. She states that the purpose of the first article is to

“review relevant scientific studies of the cognitive, emotional and behavioural processes that arise in response to information that contradicts the deep-seated beliefs that people have about 9/11”.

Given the nature of the attack and the horrific images presented by the world’s media, such as trapped individuals in the towers and others having the courage to jump. The collapses were shown live on TV and the deaths of almost 3000 individuals resulted in personal trauma. The 9/11 attack was intended to appeal to a person’s emotional state including anger and revenge.

We are deeply affected by our own mortality and fragility as humans. This is something we need to protect so we try to bolster our self-image by having a greater sense of patriotism or direct our anger at others. Any information that contradicts a person’s beliefs about their world view will prompt an emotional reaction which will trigger psychological defence mechanisms that will, in turn, hinder any discussion of the evidence. Among many people, even after ten years, this influence remains deeply ingrained and is possibly the reason why very little significant progress has been made in demanding a new investigation. Personal self-censorship has major consequences for society.

One of the issues is how we, as campaigners, set out to reduce or eliminate these mechanisms and to try to get people to be more open-minded. As it states in the article, “reminders of 9/11 can activate the attitudes that people already hold, and that the stronger they hold them, the more resistant they are to change”.

Manwell explains in the second article (Rebuilding the Road to Freedom of Reason) about how campaigners have gone through a period of openness and transformation. There is an acknowledgement that campaigners had believed the official account of 9/11 for various lengths of time. There is likely to have been a period of cognitive dissonance: do we ignore the evidence at our peril or overcome the defensive safety net and come out stronger and wiser? The conscience is activated and the moral compass is strengthened in favour of identifying with the victim’s families as well as with truth, justice, accountability and social responsibility.

Media

A person can either re-examine their beliefs or retreat into the fabricated media-controlled world. Manwell states that people who rely on the corporate media for information "may falsely believe that they are being presented with all sides of the debate … An important foundation for questioning the official story of 9/11 is the challenge to people’s beliefs about the role of the media in supporting or questioning the Government.”

Although mainstream news organisations have reported on various strands of the evidence surrounding 9/11 in the first two or three years after the attack (probably because they were reporting on important stories out of a genuine need), there appeared to have been no ability or motivation to connect the pieces together in any kind of coherent form. Indeed, since then the mainstream media has slowly ignored those early reports and turned to derogatory hit-pieces. It is the mainstream news and reporting record in the early years that matter most, just like when Dan Rather stated on 9/11 that, "for the third time today", WTC7 looked like a controlled demolition.

Collating and organising mainstream media reports has been a massive undertaking that Paul Thompson started in the early years, which still continues, in the form of the History Commons timeline that consists of hundreds of mainstream news stories.

Coincidences and discoveries

Another important area that Manwell raises is how independent events that occur at the same may lead to a subsequent re-interpretation and re-questioning of events. When we tell someone that there was a live hijacking exercise at the same time as the attacks and that inside trading occurred just prior to the attacks (to name just two), they are considered unusual but would be brushed away without a second thought. This is likely because accepting such odd coincidences will lead to a discovery that has disturbing implications a person would rather not think about.

This blog

In an attempt to expand on these articles by making further suggestions, based on other areas of research.

Self-affirmation theory

Depending on the culture, group or situation in which we find ourselves, we like to think we are law-abiding citizens with some level of social and lawful integrity. Self-affirmation theory suggests that a goal of the self is to protect and maintain that self-integrity. People are very vigilant to information that could call their integrity into question both for themselves and in the eyes of others. Whereas cognitive dissonance suggests a person will directly accommodate or reject a threat, self-affirmation involves reflecting on salient life values that are irrelevant to the threat in question, i.e. being engaged on the subject of 9/11.

Self-affirmation is about feeling positive on important issues irrelevant to what is at stake or to engage in activities that remind us of who we are. The experimental research used this idea to test how information lost its capacity to threaten self-integrity. The research paradigm involves getting participants to specify what they felt was personally important to them and write a short essay prior to the experiment on what they chose and explain why and how it made them feel good about themselves. The researchers would then ask the participants to take part in the experiment. The conceptual framework for the research is that a person would feel so good about themselves after doing the exercise that any information in the experiment that would otherwise be perceived to be threatening would lose that capacity. It is all about heightening self-esteem.

Research shows this to be the case. A study looking at US patriotism after 9/11 used an essay critical of American foreign policy ostensibly written by a person with an Arabic sounding name. The results showed that patriotic Americans were less critical of the essay if they had gone through the self-affirmation process. Another study using a mortality salience manipulation (as Manwell described in her first article, a defence mechanism which can lead to feelings of nationalism) showed that participants who had gone through the self-affirmation process eliminated this salience.

The results generally showed that participants who were self-affirmed prior to a study were less critical, could lead to greater attitude change and be more responsive to the intrinsic strengths of an argument rather than how those arguments were associated with prior beliefs. When a person feels their integrity is secure, they are far more likely to engage in a more open manner, increase openness to strong evidence against one’s position. This kind of result could be useful in attempting to persuade the public to look at the 9/11 evidence for themselves.

There are two additional areas of self-affirmation theory which could demonstrate some usefulness. There might be a motive to maintain, rather than improve, a feeling of self-worth and integrity. This can lead to the prejudice and stereotyping of others. A study on self-affirmation involving the perception of Jewish and Italian candidates for a job showed that participants who were not affirmed were more likely to be more negative, even more so toward the Jewish candidate than the Italian. Self-affirmed participants did not discriminate. The 9/11 truth movement, being in a minority, in conjunction with the common use of the phrase ‘conspiracy theorist’, means our campaign is more than likely to subject to stereotyped views if a person feels threatened (the third reason for the use of the label). They are more likely to activate stereotyped views if they are confronted by campaigners in a negative way or receive information they might perceive to be threatening to their own world view.

It is in my opinion that this is what we need to think about as campaigners. When engaging with individuals on 9/11, we need to ensure their self-esteem isn't damaged or threatened in any way.

It has taken different individuals different amounts of time to question 9/11 depending on the circumstances. I consider the word “sheeple” or describing the general uninformed population as “sheep” to be derogatory. Up until we questioned the 9/11 attack, we were once “sheep”. So describing others in that way is hypocritical, and belittling others who are not “yet awake” will only provoke a negative, hostile or defensive reaction. It is divisive and does not help our cause. Like going to see a clinical psychologist for therapy, what you should really do is allow the person to retain their integrity as much as you can. Then the chance that person will seriously consider and think about what you tell them is likely to increase considerably.

Conflict of interest and social dilemmas

There are a number of critical issues in the world we live in which could be considered as dilemmas. Whereas experimental research is carried out in artificially contrived conditions, dilemmas on the scale of 9/11 affects an entire heterogenous population where group identification is difficult and individuals are anonymous. When it comes to 9/11 we, as campaigners, would say there is no dilemma. A new investigation, while extremely painful emotionally, would quickly end the wars and likely to permanently change the way we live. For those who still accept the official story, they would rather not face the dilemma of looking at the evidence for themselves because of the fear of the consequences.

Manwell introduced automatic processing and its impact on attitudes in her first article. Something she did not introduce is how these different processes can influence our decision-making in situations where a conflict of interest may arise, “Self interest is automatic, viscerally compelling and often unconscious. Understanding one’s ethical and professional obligations to others, in contrast, often involves a more thorough process.”

In psychology, an automatic process is considered to be effortless and, since this will occur outside of awareness, the consequence is that self-interest tends to prevail. In contrast, controlled processing is likely to be evoked when we encounter unexpected information, such as being given a flyer of information about the attack. Information that is inconsistent with an automatic judgement is subject to an extra level of scrutiny. Or it may even be the opposite reaction and is immediately ripped up and thrown in the nearest bin.

Research has shown that these two different types of processes can come into conflict and involves contradictory motives which lead back to cognitive dissonance. When we give someone a flyer on 9/11 we are, in fact, subjecting them to a conflict of interest. The dilemma is to ask the question: Which is more important? My personal self-interest in how I am perceived by others or the long term interests of society? We are trying to persuade someone we are engaging with to look at the evidence. For most, it would create a conflict between what is socially good in the long term for a population and the private self-interest in the short term.

Campaigners would not consider the 9/11 issue to be a social dilemma or a conflict of interest. An individual’s short-term self interest over-rides their responsibilities towards questioning their world view probably because, as Morpheus states in The Matrix, people are so dependent on the system they will do anything to protect it. But does that really have to be the case? Is there any way in which we can engage with the public on 9/11 and not make it sound like a conflict of interest? We have to persuade an individual that it is in their interests and their responsibility that they look at the evidence and ask questions about the attack.

Majority and minority influence

It is obviously the case that the 9/11 truth movement is in the minority though, among the general population, what that percentage might be is unclear.

A recent poll reported by the UK Daily mail states that 1 in 7 (or about 15%) believe the US Government were involved, increasing to 25% among 16 to 24 year olds.

A poll carried out on behalf of Reinvestigate 9/11 suggests there might be an agreement that the official account of what happened might turn out to be wrong in important respects.

Washington has listed the trend in poll results on 9/11 in the last five years. The trend isn't from questioning the official theory to accepting it. It is the opposite. When the official account is questioned, there is no going back to accepting the official account

From poll results, attitudes towards the 9/11 campaign movement can be taken in another direction of research that also has relevance: minority versus majority arguments. People are affected differently when receiving messages from those who are perceived to be in a majority compared to those who are perceived to be in the minority.

Some Dutch investigators looked into this which I will explain in some detail. They wrote: "Attitude change on the focal issue implies (unwanted) identification with the (aversive) minority, leading recipients to suppress change on focal issues in the case of minority influence."

Conformity and the need to be popular again raises its head. In order to be liked, people are unwilling to “stand out from the crowd” (or as the Japanese like to say, “the nail that sticks out is hammered down”) and more reluctant to be perceived to be associated with others who are deemed to be in a minority group. Because 9/11 campaigners are in a minority, most individuals won’t risk being associated with the 9/11 truth campaign, because we are likely to be considered "fringe" or "extremist".

Or as Mark Twain so eloquently put it, "In the beginning of a change, the patriot is a scarce man, brave, and hated and scorned. When his cause succeeds, the timid join him, for then it costs nothing to be a patriot."

The researchers state in their paper that persuasive arguments from a majority elicit attitudes on the focal issue … while identical arguments attributed to a minority (1) have less effect in general and (2) influences attitudes on related issues more than attitudes on the focal issue.

So what are the implications for campaigning on 9/11? The obvious question the research raises is: should we make 9/11 the focal issue at all? Instead, should we be educating people about other historical events far more explicitly that may nudge individuals towards questioning 9/11 for themselves such as the Reichstag fire, Pearl Harbour, Gulf on Tonkin and Operation Northwoods? Given the mention of trying to get individuals to question the role of the mainstream media, should we be emphasising the role of the CIA and how it has been used for propaganda purposes?

The effects of prior theories on subsequent evidence

9/11 is an issue which is likely to induce sharp disagreements even among highly concerned and intelligent citizens (people who consider themselves intelligent don't like to admit they have been fooled, like Noam Chomsky).

People who hold strong opinions are likely to examine the relevant evidence in a biased manner and that data relevant to a belief are not processed impartially. In other words, judgements are based on the apparent consistency with the perceiver’s prior theories and expectations i.e. their world view and beliefs.

People tend to interpret subsequent evidence in order to maintain official beliefs by remembering the strengths, relevance and reliability of confirming evidence as well as accepting such evidence at face value.

Lord, Ross and Lepper (1979) found that proponents of capital punishment regarded a pro-deterrence study, including the quality of the research, to be more convincing. In addition, their position on capital punishment and its deterrence was more entrenched than it was at the start of the study.

Subject’s decisions about whether to accept a study’s findings at face value or to search for flaws and consider other interpretations appeared to depend on whether the results coincided with their pre-existing beliefs. When an “objective truth” is known or assumed then studies that reflect this truth may be given credence and not to studies where outcomes do not fit in with that truth.

A person’s shortcoming is their readiness in using evidence already processed in a biased manner to bolster the very theory or belief that justified the bias in the first place. People also expose themselves to be encouraged by patterns of data they should find troubling, but find it too easy to cling to beliefs that are not compatible with the latest evidence. The researchers state that “the mere availability of contradictory evidence rarely seems sufficient to cause us to abandon our prior beliefs or theories”. Is this another reason why progress towards a new investigation has been slow? Giving evidence to someone is not likely to be enough.

Spiral of silence theory

Manwell explains two theories that might be of some help in understanding how people may resist investigating 9/11. The ‘spiral of silence’ theory is a third which may also help.

This particular theory is concerned with the fear that people have of being socially isolated, and is an attempt to explain how public opinion can be treated as a dynamic process. Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann explains that to fear social isolation, like conformity, is the need to agree with other individuals. Noelle-Neumann used Asch’s conformity results to explain not only how people can be nervous in voicing what they may deem to be unpopular opinions, but how a person’s opinion change over time (Asch used a number of experiments to see what extent an individual would say the wrong answer simply in order to be liked).

Hayes et al (2008) looked at the spiral of silence of theory. They state that “knowing the attitudes and opinions of other gives us insight into the sensibility and the social veracity of our own opinions and attitudes.” They further state that “we are willing to expend valuable cognitive fuel to regularly scan the information environment so as to remain appraised of where our own opinions reside in the landscape of public opinion.”

How do we know what opinions and attitudes other people hold without asking them directly? One major source of information from which we generate opinions and attitudes is the mainstream media. Hayes et al found that those with a greater fear of social isolation were more likely to pay attention to public opinion polls, thus consistent with a central idea of the theory – that social isolation will prompt individuals to attend to relevant information about the opinion climate. In another experiment, they also found that a person is more likely to think about what others are thinking, especially family members and close friends, when they are asked to state their own opinion.

Shoemaker et al (2000) also studied the theory. They state that “people constantly observe their environment very closely. They try to find out which opinions and modes of behaviour are prevalent, and which opinions and modes of behaviour are becoming more popular. They behave and express themselves accordingly in public”. They also state that “when a person’s opinion is perceived to be in the majority, the person may speak out in public without fear of losing popularity or self-esteem. If the converse is true, the person may elect to become silent, avoiding situations in which the person will be in a confrontational embarrassing situation, such as when one’s opinion is laughed at or criticised by others.”

As far as 9/11 is concerned, people are strongly involved in self-censorship due to the fear of being public self-conscious.

A suggestion at this point is that we use not just polling results but also the trend over the last few years, on flyers and information sheets to draw attention to the number of individuals, especially the younger generation, who are beginning to question the legitimacy of the official account.

Conclusion

In the process of engaging with individuals, we ought to constantly remind ourselves of the journey we have made from accepting the official story to becoming committed campaigners. We have left the cave. Unfortunately, any attempt to rouse the interest of other prisoners within is met by ridicule or disbelief.

I think the research has raised a few suggestions some of which the movement has been doing but needs to be emphasised:

1) People don't like to admit they have been fooled and certainly don't want to be treated like idiots. It is important for campaigners not be condescending or derogatory and to allow people time and space to think things through for themselves.

2) The 9/11 evidence can be treated as a dilemma for an individual who may be nervous of the implications. I think we need to present the idea that, while emotionally painful, it is for the good of society in the long run. May be present them as a series of questions? Are you tired of people in positions of authority? Do you want to see an end to western imperialism? Do you think future generations should be able to live in a more transparent society? I don't think it is about forcing the evidence down their throats, but ask them the questions that will encourage their own investigating.

3) The truth movement is in the minority so we should emphasise the trend in poll results which indicates that people are becoming increasingly wary of the official story. Since people tend to look at opinion polls, we can use such results to our advantage. Since the minority is less likely to have an effect with the direct evidence, should we concentrate on historical information?

4) Finally, we should encourage how the mainstream media has had a negative effect on society in terms of editorial control and propaganda, and that should help to persuade individuals that information on the internet is not "fringe" or "extremist".

These are suggestions baed on the psychological research. But the only thing we can do as campaigners is to try to remain patient, don't get frustrated, sow the seeds of enlightenment and let others make up their own minds as to whether they have the courage and the conviction to leave the cave.

I hope this has been useful.

“Unfortunately no one can be told what the

Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself.”

In the words of my colleague, Ian Fantom (who writes the newsletters), keep talking!!